w post: Outwardly open, inwardly closed

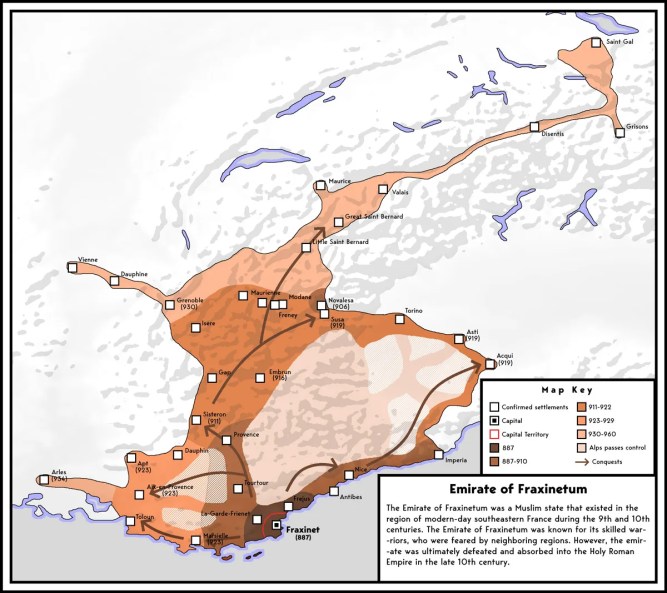

During the tenth century, barbarian raids affected large parts of what is now Switzerland. Seizing control of the western alpine passes, Saracens from the Emirate of Fraxinetum dominated the crucial arteries of trade and pilgrimage between France, Italy, and Switzerland for nearly a century. Much of Switzerland fell under their sway.

James Blake Wiener

James Blake Wiener is a world historian, Co-Founder of World History Encyclopedia, writer, and PR specialist, who has taught as a professor in Europe and North America.

The Establishment and Growth of Fraxinetum

Historians tend to see the Battle of Tours (also known as the “Battle of Poitiers”) in 732 as the high mark of Islamic expansion into Western Europe during the Early Middle Ages. Nevertheless, it is worth remembering that Islamic invasions continued in Europe well beyond the eighth century. Arabs and Berbers − referred to as “Saracens” in medieval texts − successfully invaded Crete (c. 824), Sicily (831), and Malta (870), taking advantage of political chaos across the Mediterranean Sea. They plundered the outskirts of Rome in 846, while occupying parts of Apulia between 847-871 and Campania between 885-915.

The term “Saracen”

This broad term was frequently used in medieval European texts to describe firstly the peoples of Arabia, and later those who professed Islam and lived in Islamic lands. During the the Renaissance and Age of Discovery, usage of “Saracen” was replaced by “Mohammedan” and later on by “Muslim”.The Saracens directed significant military operations against the Carolingian successor states too, launching a major naval attack on Marseilles and the towns along the estuary of the Rhône River in 831. The Saracens even managed to capture Arles in 848. The death of King Boso of Provence (r. 879-887) and the political vacuum that followed provided the Saracens the perfect opportunity to secure a new foothold in Western Europe.

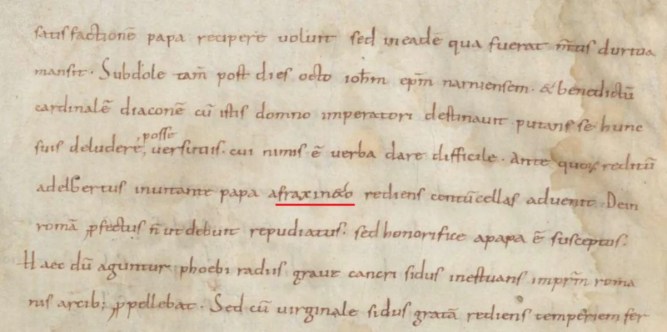

At some point around 889, a small force of perhaps 20 men laid siege to and conquered the village of La Garde-Freinet in Provence, which lies close to present-day St. Tropez. Referred to as “Fraxinetum” by early medieval European chroniclers, this Islamic settlement grew quickly thanks to its strategic location between the Gulf of Saint-Tropez and the aptly named Massif des Maures. The origins and motivations of those who populated and established Fraxinetum remain a subject of scholastic conjecture. The conquest of La Garde-Freinet may simply have been the work of shrewd pirates with knowledge of coastal and mountain fortifications. It is probable that many were of Berber origin and that some came from the Balearic Isles of Spain. Christian renegades and opportunists joined their ranks in all probability too. Aside from quick plunder, others were perhaps motivated by religious merit and the pursuit of extending the borders of Dar-al-Islam through jihad. Sources from the Islamic world are rather limited in scope on the topic of Fraxinetum. The Arab geographer Ibn Hawqal (d. 978) may have made direct references to Fraxinetum in his Surat al-ard, but the Umayyad historian Ibn Hayyan al-Qurtubi (d. 1076) does include a brief mention of it in his chronicle, Muqtabis. Many more references about Fraxinetum are found in contemporaneous Christian chronicles and records. The famed chronicler and bishop Liudprand of Cremona (920-972) mentioned Fraxinetum in his Antapodosis and Liber de rebus gestis Ottonis. He opined that the Saracens of Fraxinetum owed their allegiance to the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba.

After constructing a series of impenetrable fortifications along the Col de Maure and a garrisoned base at Fraxinetum, the Saracens could now conduct summer razzias in the direction of Burgundy, Provence, Liguria, Savoy, and Piedmont. In the east, the forces of Fraxinetum temporarily occupied and sacked Oux, Aqui, and Asti. They also took control over the Col du Mont Cenis. This was an important transalpine mountain pass and critical artery along the Via Francigena pilgrimage route, which stretched from Canterbury to Rome.

The Saracen raids were so extensive and devastating in northern Italy that the monks of Novalesa Abbey had to flee to the safety of distant Turin. In Burgundy and Provence, the Saracens sacked and looted Valence, Vienne, Toulon, Marseilles, Aix-en-Provence, Fréjus, and Embrun. Fraxinetum’s victories, in turn, attracted subsequent migration from Islamic Spain and possibly Islamic Sicily. By c. 930, Fraxinetum had grown wealthy from the accumulated booty and slaves taken from defenseless monasteries and churches.

The almighty God wished to punish the Christians through the ferocity of the heathen, a barbarian people invaded the kingdom of Provence and spread everywhere. They became very powerful and having obtained the most fortified place for their living, destroyed everything, laid waste very many churches and monasteries…Excerpt from the “Cartulaire de l’abbaye de Saint-Victor de Marseille”, c. 1005.

Fraxinetum’s Raids into Switzerland

Louis the Blind (r. 887-928), king of Provence, struggled to make war on the Saracens. His relative and chosen successor, Hugh, king of Italy, called upon the might of his brother-in-law, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (r. 917-963), to assist him in expelling the Saracens from Provence in 931.

While the Byzantines assaulted Saracen ships with their potent “Greek fire,” Hugh’s Provençal and Lombard forces attacked the Saracens in the Alps with a modicum of success. Even so, the Saracens still held several key western alpine passes and corridors: the Little St. Bernard Pass, Mt. Cenis, and that of Mt. Genèvre. The Saracens would maneuver counterattacks from them, from which they could assault much of what is present-day Switzerland. It is unclear to historians the exact routes the Saracens pursued in their raids and invasions of alpine Switzerland, but it is verified that they plundered western Valais and sacked the Abbey of Saint-Maurice d’Agaune in 939. The Frankish chronicler Flodoard of Reims (c. 893-966) confirms that attack and records further that the Saracens targeted groups of pilgrims on the way to Rome in 940. Around the same time, the Saracens destroyed the church of St. Pierre in Bourg-Saint-Pierre, which was only rebuilt in 1010. Surviving diplomatic letters state that Chur and its cathedral were ravaged in a raid around 936, along with a church in Schams. The monk and chronicler Ekkehard IV (c. 980-c.1056) attests to the presence of Saracen marauders in eastern Switzerland in his Casus sancti Galli, but he additionally delineates that the monks of St. Gallen put up a fierce resistance when attacked in 939. In contrast, the monks at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Disentis fled to the vicinity of Zürich, when the Saracens assailed their monastery around 941.

After a decade of intermittent warfare, Hugh had managed to push the Saracens back into Provence. He stood poised to vanquish the Saracens and breach their core defenses at Fraxinetum by 941. Then, he received word that his rival, Count Berengar of Ivrea, planned to invade Lombardy. Hugh now saw the Saracens as crucial in his aims to counter the political ambitions of Berengar in addition to those of Berengar’s chief supporter, Otto I, king of the Germans. Some historians suggest that Hugh may also have courted favor with the Umayyad Caliph Abd Al-Rahman III (r. 929-961), and that these diplomatic overtures prompted his sudden change of policy with regard to the Saracens. Hugh’s generous treaty of alliance permitted the Saracens to regain control over those alpine passes that led into Piedmont and Lombardy, from Mt. Genèvre to the Septimer Pass. The Saracens later assumed temporary suzerainty over the Monte Moro, the Simplon, and the Lukmanier passes as well. From their mountain basecamps, summer raiding parties regularly pillaged the Swiss countryside, striking at Chur and St. Gallen, in intervals, between c. 952-954. The Saracens even pillaged as far as the Bernese Jura in the late-950s.

How unjustly do you attempt to defend your kingdom, King Hugo! Herodes killed many innocent people, lest he be robbed of his earthly kingdom, but you let guilty people walk around free in order to get a kingdom…Liutprand of Cremona critiquing Hugo’s alliance with the Saracens of Fraxinetum in his “Antapodosis”

However, the Saracens faced competition in their quest for the spoils of plunder: the Magyars. Much like the Saracens, the Magyars took advantage of Western European social and political disarray in the wake of Carolingian fragmentation. Between 898-955, they invaded much of Western Europe and famously sacked St. Gallen in 926. Although the Saracens excelled in hand-to-hand confrontation and alpine ambushes, they were no match against the Magyars, who excelled in horsemanship and archery. Thanks to the stirrup, Magyar horsemen could easily pick off their enemies with arrows and scimitars at terrific speed. If one believes the chroniclers, roving bands of Magyars defeated the Saracens in 936 and 954. Historical sources appear to corroborate a marked decline in Saracen activity soon thereafter. The death of Abd Al-Rahman III and the ascension of his son Hakam II to the throne may hold yet another explanation for the gradual withdrawal of Saracen forces from the Alps. Unlike his father, Hakam II pursued a course of peaceful relations with his Christian neighbors in Spain and France, while waging war on the Zirids and Fatimids in North Africa instead.

Without significant materiel reinforcement from Córdoba, Fraxinetum was left exposed and vulnerable to attack. The Saracens abandoned Grenoble in 965 and Gap by 973, but they retained control over the Great St. Bernard Pass as late as 972. Fraxinetum’s fall came around 974, when Count William of Arles (c. 950-c. 993) and allied nobles from Dauphiné, Provence, Nice, and Genoa razed the citadel after the Battle of Tourtour. Those Saracens who surrendered were spared, but countless others were killed in their former mountain stronghold. Even after baptism, many were sold into slavery, while others were forced into exile.

Evaluations & Lingering Questions

Early medieval chroniclers depict the Saracen raids in the Alps as destructive and disruptive, while the Saracens, themselves, are portrayed as cunning and powerful. Since the 1800s, historians have tried to ascertain and evaluate the consequences, effects, and legacies of the Saracen invasions. The French Orientalist Joseph Toussaint Reinaud (1795-1867), in his “Invasions des Sarrazins en France, et de France en Savoie, en Piémont et dans la Suisse” (1836), explored the cooperation between locals and the Saracens, finding that there was a high degree of association between Christians and Muslims. Notable exchanges of technologies, goods, and ideas took place between the respective populations as a direct consequence. Some scholars have suggested that the Saracens introduced advanced methods in pine tar production and the cultivation of buckwheat into France as a result of their invasions. Others contend that the Saracens taught Europeans new techniques in the production of ceramics and textiles, and introduced the tambourine as a musical instrument. In Switzerland, the profusion of topographical names and surnames that seemingly allude to the historical presence of the Saracens has helped proliferate countless genealogical myths and folk legends in Valais and Graubünden. However, until more research and archaeological excavations are undertaken, they cannot all be disregarded.

Published on: 10.10.2024

Modified on: 11.10.2024

source https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2024/10/the-saracen-raids-of-early-medieval-switzerland/